ONONDAGA LAKE AMBIENT MONITORING PROGRAM

2009 ANNUAL REPORT

ONONDAGA COUNTY, NEW YORK

FINAL

NOVEMBER 2010

Prepared for:

ONONDAGA COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF WATER ENVIRONMENT PROTECTON

Syracuse, NY

Prepared by:

|

EcoLogic, LLC

Aquatic, Terrestrial and Wetland Consultants

Cazenovia, NY

Lars Rudstam, Ph.D.

Cornell Biological Field Station

Bridgeport, NY

Anchor

QEA, LLC

Liverpool, NY

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM THE COUNTY EXECUTIVE

A MESSAGE FROM THE COUNTY EXECUTIVE

Onondaga Lake is on the road to recovery.

This report of the 2009 Ambient Monitoring Program carried out by the Onondaga

County Department of Water Environment Protection (DWEP) documents significant

progress toward improving water quality and habitat conditions.

I

encourage all residents of Onondaga

County to read this

report and to take pride in the value of our investment in infrastructure

improvements.

As in 2008, the 2009 AMP annual report is a concise summary of

major findings with links to supporting information. This paperless format was

developed to advance two objectives: first, to reach a broader audience, and

second, to continue to find ways to reduce our environmental footprint, through

our commitment to green initiatives. We are confident that this format will

enable more of our County leaders and citizens to become better informed

regarding the condition of Onondaga

Lake and its watershed.

Additional program information, including annual reports from previous years,

can be found on the County web site www.ongov.net/wep

Joanne C. Mahoney

Onondaga County Executive

_____________________________________________________________________________________

A MESSAGE FROM THE

COMMISSIONER OF WATER ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION

The Department of Water Environment Protection is responsible

for collecting and treating wastewater from homes and businesses throughout the

County. As Commissioner, I am proud to lead our dedicated staff under a name

that reflects Onondaga County’s firm commitment to

protecting the water resources we all share. The Department is required to

complete an intensive survey of water quality conditions in the Onondaga Lake watershed each year. This

publication is a summary of the findings of the 2009 Ambient Monitoring Program

(AMP). 2009 marked the 40th consecutive year that Onondaga County

successfully completed a monitoring program of Onondaga Lake

and adjacent waters. Results of this long-term monitoring effort are used to

track how Onondaga

Lake is responding to

pollution abatement activities. Current conditions and trends in water quality

and the lake’s biological community are highlighted in

this

document. Comments on this report are encouraged and may be directed to Jeanne

C. Powers at 315-435-2260 or email JeannePowers@ongov.net

Patricia M.

Pastella, P.E., BCEE

Commissioner

Key

Features of this Report

This report presents the findings of Onondaga County’s Ambient

Monitoring Program (AMP) for 2009. The County’s annual monitoring program is

designed to evaluate compliance with water quality standards and trends as

improvements to the wastewater collection and treatment infrastructure are

completed. Each year, the Onondaga

County Department of Water Environment Protection collects extensive water

quality and biological data to characterize Onondaga Lake and its

watershed. This summary report of 2009

conditions provides a synopsis of the extensive data to the many stakeholders

interested in Onondaga

Lake.

The 2009 report was prepared and distributed as an electronic

document. Key results and supporting tables and graphics are included in the main

document, with links to supporting tables, technical reports and graphics in an

electronic library. The report and supporting files are available on CD and on

the Onondaga County web site www.ongov.net. Throughout the document, the reader will

find hyperlinks to more detailed tables, graphs and reports. Simple definitions of many of the technical

terms are included (roll the computer mouse over a highlighted term). A folder

icon at the end of each section (illustrated below) provides links to the

section of the electronic library where additional materials are archived.

Once in the library of supporting

documents, the reader can navigate back to the main report using web browser

navigation tools. There are more than

500 supporting tables and graphics in the library of supporting materials.

While each hyperlink has been checked, it is possible that some features may

not be enabled on every computer’s

operating system. Feedback on the functionality of the electronic

features of the document is welcome, please contact JeannePowers@ongov.net with comments.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary

1.

Introduction to the AMP

1.1

Regulatory requirements

1.2 Ambient Monitoring Program Design

1.3 Turning Data into Information: Metrics

1.4 Mathematical modeling

1.5 Timeline of Onondaga Lake and Watershed

Events, 1998-2009

2. Onondaga Lake and its Watershed

3. Tributary

Results: 2009 Water Quality Status and Trends

3.1 Climatic Conditions

3.2 Tributary Water Quality and Annual Loads

Compliance with Ambient Water Quality Standards

Compliance with Metro SPDES Permit

Flows and Loads

Storm Events

Wet and Dry Weather Events

Trends

4. Onondaga Lake: 2009 Water Quality Status

and Trends

4.1 Trophic State Indicator Parameters

Total

Phosphorus (TP)

Chlorophyll-a

Secchi Disk Transparency

Trophic State Index

4.2 Ammonia and Nitrite

4.3 Recreational Quality

4.4 Metro Improvements and Lake Response

4.5 Seneca

River

5. Biology and Food Web: 2009 Results and

Trends

5.1

Phytoplankton

5.2

Macrophytes

5.3

Zooplankton

5.4 Zebra and Quagga Mussels

5.5 Fish

Richness and Diversity

Reproductive Success

Recreational Fishery

Abnormalities

6. Integrated Assessment of the Food Web

7. Progress with Related Initiatives

8. Emerging Issues and Recommendations

9. Literature

Cited

LINK TO LIBRARY FILES

LIST

OF TABLES AND FIGURES BY SECTION

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Table EX-1 Summary

of Metrics, Onondaga Lake 2009.

SECTION 1: Introduction to

the AMP

Table 1-1. Summary of Current Fish Consumption

Advisories for Onondaga Lake.

Table 1-2 Metro

Compliance Schedule.

Table 1-3 CSO

Compliance Schedule.

Table 1-4 Data Analysis and Interpretation Plan.

Table 1-5 Summary

of metrics used to evaluate progress toward improvement.

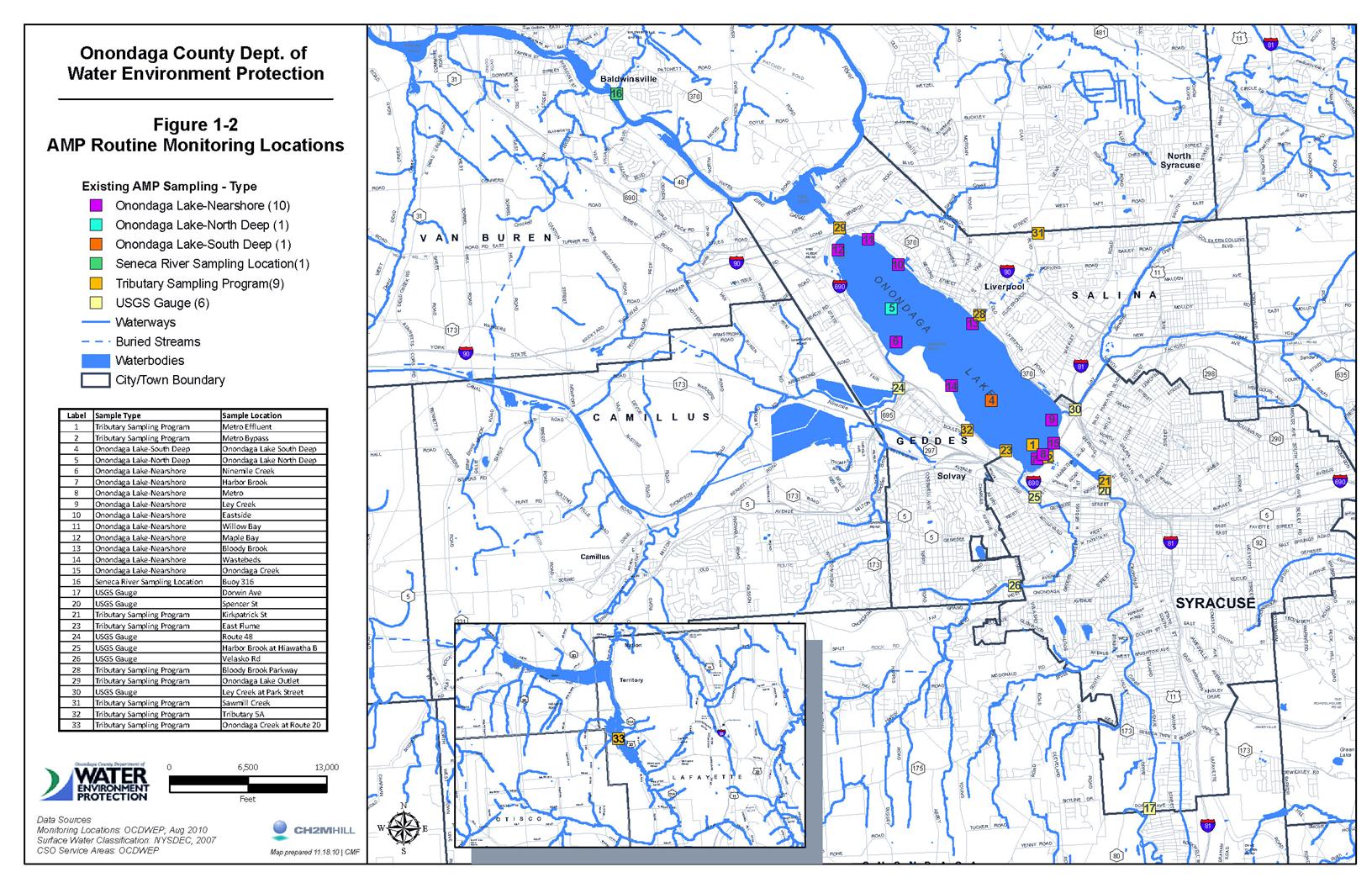

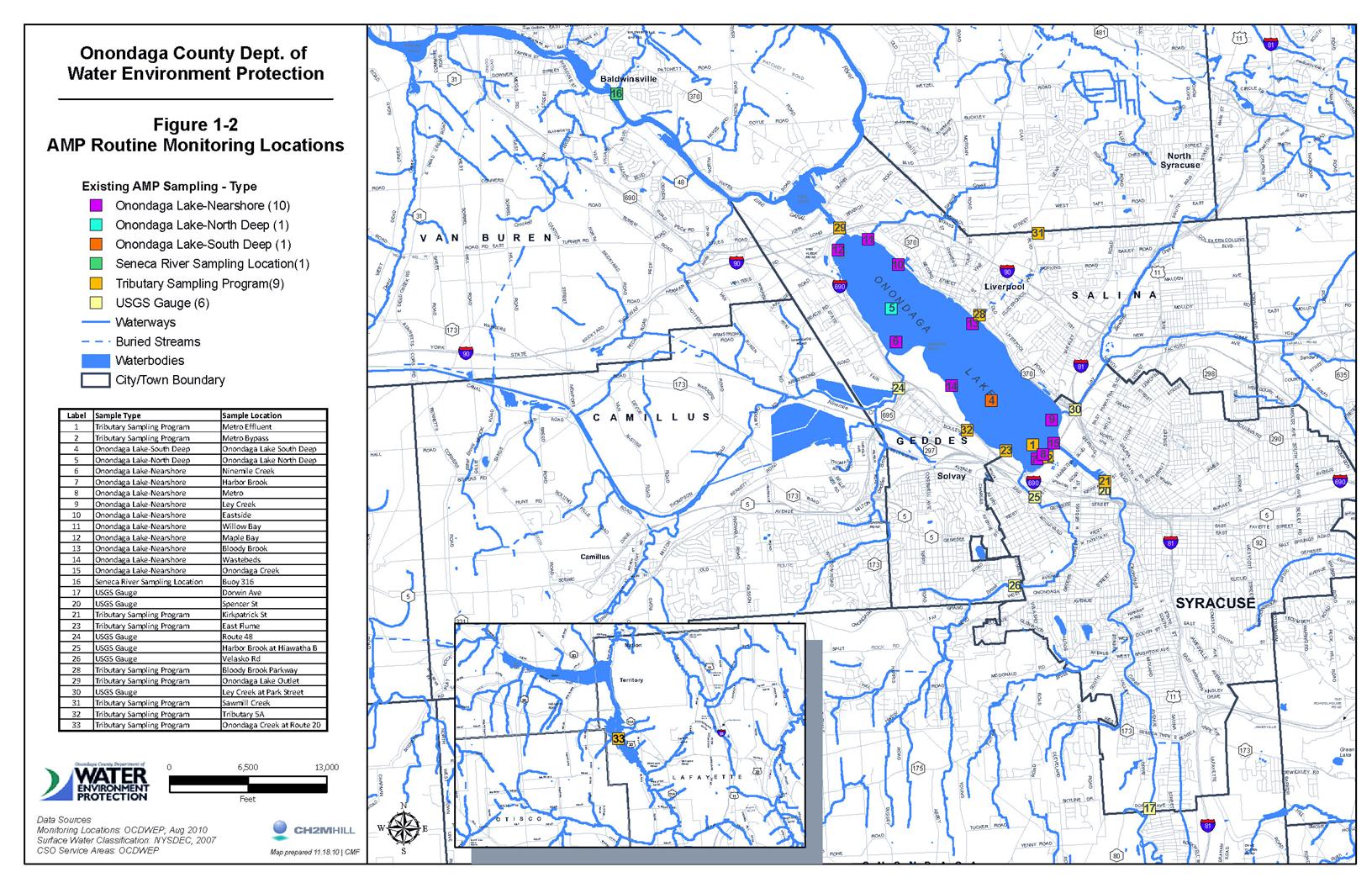

Figure 1-1 Tributary

and Lake Regulatory Classification and Subwatershed Boundaries.

Figure 1-2 Map

of monitoring locations, Onondaga Lake and tributaries.

SECTION 2: Onondaga Lake

and its Watershed

Table 2-1 Morphometric

characteristics of Onondaga Lake.

Figure 2-1 Hydrologic

input to Onondaga Lake, as percent of total.

Figure 2-2 Land Cover Classes, 2001, Onondaga Lake

Watershed.

SECTION

3: Tributary Results: 2009 Results and Trends

Table 3-1 Percent

of Onondaga Lake tributary sample results in compliance with NYS water quality

standards, 2009.

Table 3-2 Flow-weighted

average concentration of selected parameters, 2009, Onondaga Lake tributaries.

Table 3-3 Annual loading of selected water quality

parameters to Onondaga Lake, 2009.

Table 3-4 Percent annual loading contribution by

gauged inflow, 2009.

Table 3-5 Tributary and Metro Total Phosphorus (TP)

Loading to Onondaga Lake, pre-ACJ and post-ActiFlo implementation.

Table 3-6 Tributary and Metro Soluble Reactive

Phosphorus (SRP) Loading to Onondaga Lake, pre-ACJ and post-ActiFlo

implementation.

Figure 3-1 Metro

NH3-N, monthly average discharge compared to permit limit.

Figure 3-2 Metro

effluent compliance for total phosphorus concentration, 12-month rolling

average.

Figure 3-3 Metro

and Tributary Sources of TP to Onondaga Lake, 1998 to 2009.

Figure 3-4 Metro

and Tributary Sources of SRP to Onondaga Lake, 1998 to 2009.

Figure 3-5 Total

phosphorus external loading to Onondaga Lake (Water Year) compared with South

Deep total phosphorus concentrations (summer) in upper waters.

Figure 3-6 Metro

Loading of Ammonia, Nitrite, Nitrate and Organic Nitrogen, 1998‐2009.

Figure 3-7 Onondaga

Lake Ammonia Sources, 1998 and 2009.

SECTION 4: Onondaga Lake:

2009 Status and Trends

Table 4-1 Percent

of Ammonia Measurements in Compliance with Ambient Water Quality Standards,

Onondaga Lake, 1998-2009.

Table 4-2 Nearshore

Secchi disk transparency statistical summary for Onondaga Lake, 2009.

Figure 4-1 Onondaga

Lake Summer Average Total P Concentration (0‐3m), 1998‐2009.

Figure 4-2 Onondaga

Lake Summer Algal Bloom Frequency, 1998‐2009.

Figure 4-3 Onondaga

Lake Chlorophyll‐a

Concentration, 1998-2009.

Figure 4-4 TP

and Chlorophyll-a concentrations,

Onondaga Lake 2007-2009 compared with Oneida and Finger Lakes.

Figure 4-5 Onondaga

Lake Secchi Disk Transparency, January‐December, 2009.

Figure 4-6 Carlson

Trophic State Index (TSI) Onondaga Lake, 1998- 2009.

Figure 4-7 Onondaga

Lake Fecal Coliform Bacteria Abundance, Summer Geometric Mean, 1999‐2009.

Figure 4-8 Onondaga

Lake Fecal Coliform Bacteria Compliance, April – October 2009.

Figure 4-9 Relationship

between TP Loading (all sources) and Onondaga Lake TP Concentration, 1990‐2009.

Figure 4-10 Nitrogen:

Phosphorus Ratio, 1998‐2009.

Figure 4‐11 Onondaga Lake Minimum DO in upper waters (0-3m)

during fall mixing period, 1998‐2009.

Figure 4-12 Comparison of soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP)

and nitrate-N concentrations with dissolved oxygen concentrations in South Deep

lower waters of Onondaga Lake during 2009.

Figure 4-13 Three

Rivers System Study Area.

SECTION 5: Biology and

Food Web: 2009 Results and Trends

Table 5-1 2009

Macrophyte Field Survey Results.

Table 5-2 List of Fish Species Identified in Onondaga

Lake, 2009

Figure 5-1 Reduction

in Onondaga Lake phytoplankton standing crop, 1998 - 2009.

Figure 5-2 2009

Proportional biomass of phytoplankton divisions in Onondaga Lake.

Figure 5-3 Onondaga

Lake Phytoplankton Community Structure and Biomass, February-December 2009.

Figure 5-4 Onondaga

Lake South Deep, comparison of diatoms and silica concentrations in 2009.

Figure 5-5 Average

biomass of zooplankton, proportion of major groups across time.

Figure 5-6 Biomass

of different Daphnia species in Onondaga Lake.

Figure 5-7 Time

trends in average size of all crustaceans from 1999 to 2009 in Onondaga Lake.

Figure 5-8 Average

crustacean zooplankton length (mm) in Onondaga Lake in 2009.

Figure 5-9 Onondaga

Lake Dreissenid Mussel Average Density and Biomass with Standard Deviation,

2002-2009.

Figure 5-10 Onondaga

Lake Relative Abundance of Dreissenid Mussels, 2002-2009.

Figure 5-11 Comparison of DELTFM for all fish evaluated

with brown bullhead only.

SECTION 6: Integrated

Assessment of the Food Web

Figure 6-1 Food web effects on water clarity

SECTION 7: Progress with

Related Initiatives

No

figures or tables

SECTION 8: Emerging

Issues and Recommendations

No

figures or tables

SECTION 9: Literature

Cited

List of Acronyms

Executive

Summary

The 2009 Annual Report of

Onondaga County’s Ambient Monitoring

Program (AMP) provides an overview of the

results of the extensive monitoring effort underway to characterize Onondaga Lake and its watershed. Conducted annually since 1970,

the AMP represents an unparalleled investment in long-term monitoring of a

complex aquatic ecosystem.

In 1998, an Amended Consent Judgment (ACJ) between Onondaga County, New York

State and Atlantic States Legal Foundation was signed to resolve a lawsuit

filed against Onondaga

County for violations of

the Clean Water Act. The lawsuit alleged that discharges from the Metropolitan

Syracuse Wastewater Treatment Plant (Metro) exceeded the facility’s permitted discharge limits,

and that overflows from the combined

sewer system (CSOs) were not in compliance with state and federal

requirements. The ACJ obligates the

County to undertake a phased program of wastewater collection and treatment

improvements, monitor water quality response, and report annually on progress

towards compliance. This annual report fulfills the requirement for monitoring

and reporting. The ACJ has been amended four times since 1998 to reflect

changes in regulations, technology and environmental conditions, most recently

by stipulation

in November 2009. Among other

requirements, the November 2009 amendment extends the schedule of required

infrastructure improvements and monitoring through the year 2018.

The AMP is designed to document the lake’s response to

pollution control measures. Samples are collected throughout the entire

watershed to identify sources of materials (nutrients, sediment, bacteria and

chemicals) to the lake. An intensive in-lake monitoring program examines water

quality conditions and the interactions between Onondaga

Lake and the Seneca River.

Data are evaluated for compliance with water

quality standards

and analyzed for trends. In addition to

the water quality monitoring effort, the AMP examines the nature of the lake

ecosystem by characterizing the species composition and abundance of fish,

phytoplankton, zooplankton, benthic invertebrates, aquatic plants and

dreissenid (zebra and quagga) mussels.

Excessive

discharges of municipal and industrial wastewaters, structural modifications

resulting in altered water levels, loss of wetlands, and runoff from urban and

rural areas have degraded the quality of Onondaga Lake. Contact recreation has been precluded by

elevated bacteria counts, algal blooms from excessive phosphorus and poor water

clarity. Conditions for aquatic life

were compromised by high ammonia and nitrite concentrations, low dissolved

oxygen levels, and lack of habitat. Onondaga Lake’s degraded water quality

resulted from multiple sources of pollution. Increasingly stringent regulations

and major investments by the public and private sectors have reduced the

pollutant inputs to Onondaga

Lake, resulting in

improved water quality and habitat conditions.

In

light of the lake’s

water quality conditions, the primary focus of

the improvements to the wastewater treatment system has been to provide a

higher level of treatment for ammonia and phosphorus at Metro. Two new

treatment systems have been brought on line to reduce Metro’s discharge of

ammonia and phosphorus to Onondaga

Lake. The Biological

Aerated Filter (BAF) system has resulted in year-round nitrification

(conversion of ammonia to nitrate) of the wastewater. This innovative

technology, which became fully operational in 2004, has resulted in a 98%

decrease in Metro’s

ammonia loading to the lake. Phosphorus removal is achieved using a physical-chemical High-Rate Flocculated

Settling (HRFS) technology, known as Actiflo. The system came on line in 2005

to meet an interim effluent limit of 0.12 mg/L of total phosphorus. This technology has resulted in an 86%

decrease in Metro’s

total phosphorus loading to the lake. As part of the November 2009, fourth

stipulation to the ACJ, the total phosphorus discharge limit from

Metro will be revised downward to 0.10 mg/L, effective in November, 2010. In

addition to these improvements focused on ammonia and phosphorus, the

technology employed for disinfecting Metro effluent has been upgraded from

chlorination/dechlorination to an ultraviolet disinfection system.

The

2009 results document the continued significant improvements in Onondaga Lake brought about by these reductions

in ammonia and phosphorus inputs from Metro. Water quality has improved

dramatically; nutrient levels are reduced and dissolved oxygen has increased.

No algal blooms were evident; the lake water was generally clear and

aesthetically appealing. Total phosphorus concentrations averaged 17 µg/L over

the summer of 2009 in the lake’s upper waters, comparable to conditions in nearby Oneida Lake and several of the Finger

Lakes. The summer of 2009 marks the second consecutive year that

the total P concentration in Onondaga Lake waters has complied with the state’s guidance value

of 20 µg/L, which was established to protect recreational uses and drinking

water supply. Bacteria counts in the Class B segment of the lake shoreline

remained within limits set for water contact recreation. Ammonia N concentrations have been in full

compliance with NYS standards in the lake’s upper waters since 2004, and at all

water depths since 2007.

Clearer

water allows light to penetrate deeper into the lake, and fosters the

proliferation of macrophytes (rooted aquatic plants and bottom-dwelling algae)

in nearshore shallow waters, to a water depth of six meters. The macrophyte community has also become

more diverse, as more species of plants have colonized the nearshore waters of

the lake. As these macrophyte beds have

spread around the perimeter of the lake, they have brought improved habitat

conditions. The populations of gamefish

such as largemouth and smallmouth bass have increased steadily since 2000.

The

2009 report highlights an expanded review of the lake’s fish community, tracking

changes over a full decade of AMP biological

monitoring (2000 –

2009). Overall, there has been an increase in

the quantity and quality of habitat, both littoral and pelagic, available to fish species. This has resulted in a slight increase in the

number of species present and a more even distribution of fish throughout the

lake. Many fish species, particularly

those associated with vegetated habitats, are also increasing in

abundance. The aquatic food web within

the lake continues to include new species, both native and non-indigenous

(exotic), with increasingly complex pathways of material and energy transfer

among the life stages of the biota. This increasing complexity with regard to

energy sources and energy flow results in an ecosystem that may be more

resilient to environmental stress. The

results of the 2009 AMP indicate that this is an ongoing process and that more

changes are likely to occur. As lake

water quality continues to improve, resulting in more diverse and higher

quality habitat conditions, increases in aquatic species diversity, abundance, and interrelatedness can also be expected.

Segments

of streams flowing into Onondaga

Lake also exhibit

degraded water quality and habitat conditions. The ACJ has required investment

in improvements to the wastewater collection infrastructure as well as at

Metro. These improvements are improving water quality and habitat conditions in

segments of the lake tributaries affected by combined sewer overflows. Four

strategies have been employed to eliminate wet weather discharges from the

combined sewer system; these methods include separating sewers, constructing

regional treatment facilities, capturing floatable materials and maximizing

system storage capacity. During 2009, County facilities and other urban areas

began to implement green infrastructure solutions to help manage urban storm

runoff. Green infrastructure encourages infiltration, capture and reuse of

storm runoff before it enters the sewer system. By preventing storm water

runoff from entering the combined sewers, more capacity is available for

sanitary sewage flow to reach Metro for treatment. The fourth stipulation

includes specific requirements and milestone dates for capturing an increasing

percentage of the annual stormwater volume. A “Save the Rain” initiative is

underway to educate watershed residents about ways to capture and use rain water.

Water

quality conditions in the Seneca

River during 2009 were

comparable to those measured in previous years. Although the proliferation of

dreissenid mussels continues to affect water quality conditions, relatively

high stream flows during the summer of 2009 prevented prolonged conditions of

low dissolved oxygen. Ammonia and nitrite concentrations in the monitored

segments of the Seneca

River were in compliance

during 2009.

Onondaga County Department

of Water Environment Protection, in consultation with NYSDEC and the Onondaga

Lake Technical Advisory Group, has developed a suite of metrics to help organize and report on the extensive AMP

data set each year. These metrics relate to the lake’s designated “best use”

for water contact recreation, fishing and protection of aquatic life. The 2009

results (Table EX-1) document substantial progress toward attaining the

designated uses in Onondaga

Lake.

|

Table EX-1. Summary of 2009 Onondaga Lake Conditions.

|

|

Restoration

Goal

|

Measured

By

|

2009

Results

|

Significance

|

|

Suitability for Water Contact

Recreation

|

|

Indicator bacteria

|

Fecal colilform bacteria abundance

|

Met NYSDEC standards for water

contact recreation in Class B segments (200 cfu/ 100 mL, geometric mean of at

least 5 samples/month)

|

Class B segments of the lake

exhibit water clarity and bacteria levels that would support swimming,

boating, waterskiing and other types of contact recreation. Class C segments

of the lake, which are close to the major tributaries, periodically exhibit

elevated bacteria and reduced water clarity conditions after storms.

|

|

Water clarity

|

Secchi disk transparency

(nearshore stations)

|

Met NYS Dept. of Health swimming

safety guidance value (1.2 m water clarity) for water contact recreation in

Class B segments

|

|

Aesthetic Appeal

|

|

Water clarity

|

Secchi disk transparency

(mid-lake station)

|

Average June – Sept Secchi disk,

South Deep (mid-lake station): 3.2 m

|

Total

phosphorus (total P) concentration in the lake’s upper waters during summer

(June- Sept) 2009 was 17 ug/L, within the NYSDEC guidance value of 20 ug/L

established to protect the aesthetic quality of lakes and ensure their

suitability for recreational use.

The

low total P resulted in low algal abundance and clear water. The lake was

free of nuisance algal blooms, and cyanobacteria abundance was very low.

|

|

Algal blooms

|

Chlorophyll-a

Total phosphorus in the upper

waters, June – Sept

|

June

– Sept chlorophyll-a @ South Deep

(mid-lake station): 5.9 ug/L

Low

algal abundance throughout the entire recreational period, no blooms

Summer average TP:

17 ug/L

|

|

Algal community

structure

|

Abundance of cyanobacteria

(blue-green algae)

|

<1% of the algal community

was comprised of cyanobacteria

|

|

Aquatic Life Protection

|

|

Ammonia

|

Measured in-lake concentrations,

year-round, all depths

|

100% of measurements met NYS

standards, all depths

|

The 2009 water quality

conditions fully support a diverse warm water aquatic biota. Prior to the ACJ

improvements to the wastewater collection and treatment system, elevated

concentrations of ammonia and nitrite N, and low concentrations of DO during

fall mixing, were measured in Onondaga Lake. These water quality parameters

are now in full compliance with ambient water quality standards established

to protect even the most sensitive species and life stages.

|

|

Nitrite

|

Measured in-lake concentrations,

year-round, all depths

|

100% of measurements met NYS

standards, all depths

|

|

Dissolved oxygen (DO)

|

In-situ buoys and frequent field

profiles during fall mixing (turnover), when historically conditions in Onondaga Lake have been most stressful to

aquatic life

|

7.2 mg/L average DO during fall

mixing, minimum 6.9 mg/L

|

|

Sustainable Recreational Fishery

|

|

Habitat quality

|

Cover and density of aquatic

plants (macrophytes)

Deep water dissolved oxygen

during stratified period

|

Approximately 50% of the

littoral zone exhibited dense macrophyte growth.

The littoral zone is defined as the nearshore

area where light reaches the sediment surface and is thus suitable for the

growth of rooted aquatic plants.

Summer anoxia in hypolimnion

|

Coverage in this range provides

high quality habitat for fish reproduction and rearing; current conditions

are near-optimal for smallmouth and largemouth bass.

Lack of well-oxygenated cold

water limits habitat for resident cold water fish community.

|

|

Fish reproduction

|

Reproduction of target species:

· bass and sunfish

· yellow perch

· black crappie

· rock bass

· walleye and northern pike

|

Occurring:

· bass and sunfish

· yellow perch

· rock bass

No evidence:

· black crappie

· walleye

· northern pike

|

Fish reproduction for several

target species has not been observed in the lake. Adult populations of these

species are stable and, in some cases, increasing. The lack of suitable

spawning habitat, not water quality, appears to be the limiting factor in

fish reproduction in the lake. Restoration of habitat is underway as part of

the Honeywell lake cleanup project.

|

|

Fish community structure

|

Percent of fish species

intolerant or moderately intolerant of pollution

|

4%

|

Most of the Onondaga Lake

fishes are warm water species, and are relatively tolerant of pollution.

Consequently, the percentage of fish species intolerant or moderately

intolerant of pollution is unlikely to exhibit a large increase in the

future.

|

1. Introduction to the AMP

1.1 Regulatory

Requirements

The 2009 Annual AMP report has been prepared and submitted

to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) to

comply with a judicial requirement set forth in the 1998 Amended Consent

Judgment (ACJ) between Onondaga County,

New York State and Atlantic

States Legal Foundation. The ACJ, signed in 1998, has been modified four times,

most recently by stipulation in November 2009. The ACJ

requires a series of improvements to the County wastewater collection and

treatment infrastructure, and an extensive monitoring program to document the

improvements achieved by these measures. Onondaga County Department of Water

Environment Protection monitors the quality of Onondaga

Lake, the lake tributaries, and a

segment of the Seneca

River as part of the

Ambient Monitoring Program (AMP); the program is focused on evaluating

compliance with ambient water quality standards, the nature of the aquatic

habitat, and trends toward improvement.

The NYSDEC is responsible for managing water resources

throughout NY State. As part of this responsibility, NYSDEC classifies surface

waters, including lakes, rivers, streams, embayments, estuaries and groundwater

with respect to their best use.

Monitoring results are evaluated on a regular basis to determine whether

designated uses are supported, and if not, the factors precluding use

attainment. Onondaga

Lake was included on the

state’s inaugural listing of impaired waters in 1998 due to its elevated levels

of ammonia, phosphorus and bacteria, and for its low concentrations of

dissolved oxygen (DO) in the upper waters during fall mixing. The NYSDEC most

recent listing of impaired waters includes several

segments of tributaries to Onondaga

Lake. Waterbodies are

placed on this list when there is evidence that water quality conditions are

not in compliance with applicable standards, and/or the water bodies do not

support their designated use.

Water flows to Onondaga

Lake from a large land

area drained by multiple tributaries, as illustrated in Figure 1-1. Several

outfalls of treated municipal and industrial wastewater and stormwater also

flow into the lake; Tributary 5A and the East Flume flow into Onondaga Lake

along its western shoreline, and Metro effluent enters the lake at the southern

shoreline. The locations of these three inflows are shown in Figure 1-2.

Onondaga

Lake and its tributaries are

currently classified to include Class B and Class C waters. The best usages of Class B waters are primary and

secondary water contact recreation and fishing. Primary water contact

recreation includes activities that immerse the body in the water, such as

swimming; secondary water contact recreation includes activities without full

immersion, such as boating. In addition, Class B waters shall be suitable for

fish, shellfish, and wildlife propagation and survival. The best usage of Class

C waters is fishing. These waters shall also be suitable for fish, shellfish and

wildlife propagation and survival. Class C waters shall be suitable for primary

and secondary water contact recreation, although other factors may limit the

use for these purposes.

For many years, Onondaga Lake did not support its designated uses

due to excessive discharges of municipal and industrial wastewaters and

uncontrolled storm water runoff. Swimming was banned in 1940 due to elevated

bacteria counts and poor water clarity.

Conditions for aquatic life were compromised by high ammonia concentrations

and low dissolved oxygen. Fishing was

banned in Onondaga

Lake in 1972 because of

mercury contamination. The ban was lifted in 1986 and modified into a “catch

and release fishery”; that is, recreational fishing was permitted but

possession of lake fishes was not. Further modifications to the fish

consumption advisories and regulations have occurred over the years, and there

is no longer a blanket restriction on possession of all fish. The current advisory sets forth consumption limits on specific species, and

includes the warning that women under age 50 and children under age 15 should

not consume fish from Onondaga

Lake. Everyone else is advised to eat no walleye of any size, nor largemouth or smallmouth

bass over 15 inches. New in 2010 is the advisory to not eat any carp, channel

catfish or white perch from Onondaga

Lake. The specific advisory for Onondaga Lake

also applies to tributaries and connected waters if there are no barriers to

passage, such as dams or falls.

|

Table

1-1. Summary of Current Fish Consumption Advisories for

Onondaga Lake.

|

|

Lake

|

Species

|

Advisory

|

Chemicals

of Concern

|

|

Onondaga Lake

|

Largemouth

bass and smallmouth bass over 15" and walleye

|

Don't eat

|

Mercury,

PCBs

|

|

Carp,

channel catfish and white perch

|

Don't eat

|

PCBs,

Mercury, Dioxin

|

|

All

fish not listed

|

Eat

up to one meal per month

|

Mercury,

PCBs

|

|

Brown

bullhead and pumpkinseed

|

Eat

up to four meals per month

|

Mercury,

PCBs

|

Some areas of Syracuse

are served by combined

sewer systems which carry both

sewage and storm water in a single pipe. These pipes can overflow during

periods of heavy rain and snowmelt, allowing a mixture of stormwater and

untreated sewage to flow into creeks and ultimately reach Onondaga Lake.

The sewer system was originally designed to overflow to prevent sewage from

backing up into streets and basements, thereby protecting public health. The

combined sewer overflows (CSOs) direct bacteria, floating trash, organic

material, nutrients and solid materials to the waterways.

A comprehensive program to address

the sources of pollution that preclude attainment of the designated uses is

underway. Onondaga County, New York State Department of Environmental

Conservation (NYSDEC) and Atlantic States Legal Foundation entered into the

1998 Amended Consent Judgment (ACJ) to resolve a lawsuit filed against Onondaga

County alleging violations of the Clean Water Act; namely, that discharges from

the Syracuse Metropolitan Wastewater Treatment Plant (Metro) were in violation

of the facility’s discharge permit, and the combined sewer overflows (CSOs) did

not comply with state and federal regulations.

The ACJ has been modified over the years to respond to new technologies

and actual water quality conditions. As of 2010, the County is required to

undertake a phased program of wastewater collection and treatment improvements

extending through 2018 (Tables 1-1 and 1-2).

|

Table 1-2 Metro

Compliance Schedule.

(ppd = pounds per day; mg/L = milligrams per liter)

|

|

Parameter

|

SPDES Limit

|

Effective Date

|

Achieved Date

|

|

Ammonia

|

Stage I :

8,700

ppd (7/1-9/30)

13,100

ppd (10/1-6/30)

|

January 1998

|

January 1998

|

|

|

Stage II:

2 mg/L (6/1-10/31)

4 mg/L (11/1-5/31)

|

May 2004

|

February 2004

|

|

|

Stage III:

1.2 mg/L (6/1-10/31)

2.4 mg/L (11/1-5/31)

|

December 2012

|

February 2004

|

|

Total

Phosphorus

|

Stage I :

400

ppd

(12-month

rolling average)

|

January 1998

|

January 1998

|

|

|

Stage II:

0.12 mg/L

(12-month rolling average)

|

April 2006

|

April 2006

|

|

|

Revised Interim Stage II:

0.10 mg/L

(12-month rolling average)

|

November 2010

|

Pending

|

|

|

Stage III:

0.020 mg/L

(or as modified by TMDL)

|

December 2015

(or as modified

by TMDL)

|

Pending

|

|

Table

1-3. CSO Compliance

Schedule.

|

|

Project Phase

|

Goal

|

Effective Date

|

|

Stage

I

|

Capture for treatment or

eliminate 89.5% of combined sewage* during precipitation, within the meaning of EPA’s

National CSO Control Policy

|

Dec 31, 2013

|

|

Stage

II

|

Capture for treatment or

eliminate 91.4% of combined sewage during precipitation, within the meaning of EPA’s

National CSO Control Policy

|

Dec 31, 2015

|

|

Stage

III

|

Capture for treatment or

eliminate 93% of combined sewage during precipitation within the meaning of EPA’s

National CSO Control Policy

|

Dec 31, 2016

|

|

Stage

IV

|

Capture for treatment or

eliminate 95% of combined sewage during precipitation within the meaning of EPA’s

National CSO Control Policy

|

Dec 31, 2018

|

|

*on a system-wide annual average basis

(per

fourth stipulation to ACJ, Nov. 2009)

|

There are three elements to the ACJ: (1) improvements to Metro, primarily

to reduce phosphorus and ammonia loading, (2) improvements to the wastewater

collection infrastructure to reduce combined sewer overflows (CSOs); and (3)

monitoring the surface waters to evaluate the effectiveness of the improvements

to the wastewater collection and treatment system. Onondaga County

has designed the AMP to provide the data and information needed to document the effectiveness of the controls on

the municipal pollution sources. NYSDEC reviews and approves the annual AMP work plan, participates in technical work group meetings and

reviews and approves the annual report.

The industrial pollution

impacts are also being addressed; projects to intercept and treat contaminated groundwater, remove contaminated

sediments and restore habitat are underway. This effort is spearheaded by

Honeywell International with oversight by state and federal officials. A detailed description of the

Honeywell remedial projects planned for the Onondaga Lake

watershed is on the NYSDEC web site http://www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/48828.html.

1.2 Ambient Monitoring Program Design

The AMP is designed to

identify sources of materials (nutrients, sediment, bacteria and chemicals) to

the lake, evaluate in-lake water quality conditions, and examine the

interactions between Onondaga Lake and the Seneca River.

Representative samples are collected by trained field technicians from a

network of permanent sampling locations along the lake tributaries, nearshore

and deep stations in Onondaga Lake, and along the Seneca River

(Figure 1-2). Data are evaluated with respect to compliance with water quality

standards and trends.

In addition to the water quality monitoring effort, the

AMP examines the health of the lake ecosystem by sampling fish, phytoplankton,

zooplankton, benthic invertebrates, aquatic plants and dreissenid (zebra and

quagga) mussels. The health of the watershed is assessed as well, through an

integrated program that focuses on identifying potential sources of materials

such as nutrients, sediment and bacteria.

Biological indicators of stream condition are evaluated as well. A Data Analysis and Interpretation Plan (DAIP) (Table 1-3) guides program

design and is a component of the annual workplan, and consequently subject to

NYSDEC review and approval.

A rigorous Quality Assurance/Quality Control program

is in place. The AMP workplan is subject

to NYSDEC review and approval each year. Samples are collected by trained

technicians and analyzed in a laboratory certified by the NYS Department of

Health. Internal and external audits are conducted, blanks and duplicates are evaluated, and the

results are presented in the annual AMP report. Experts serving on the Onondaga Lake Technical Advisory Committee (OLTAC) review the data and

interpretive reports each year and make recommendations.

An expert on statistics and lake water quality periodically reviews

the AMP design for its power to detect trends. That is, what sampling frequency

and duration are needed to differentiate a significant change, given the

magnitude of natural variation? This analysis, referred to as the Statistical Framework, has been completed for water quality and biological

parameters by Dr. William W. Walker,

a member of OLTAC. Dr. Walker’s evaluations of the AMP are available on his web site www.wwwalker.net/onondaga.

Each year, OCDWEP tests over 20,000 water

samples and examines several thousand biological samples. The County has

invested in the creation of custom databases to facilitate analysis and

reporting. The 2009 data have been appended to the water quality database,

which is a repository of tributary (T), lake (L) and river (R) data collected

since 1968. An integrated biological database is used to manage results of the

fisheries, phytoplankton, zooplankton, macroinvertebrate and macrophyte

monitoring efforts.

Table 1-4. Data Analysis and Interpretation Plan.

|

Parameters

|

Sampling

Locations

|

Compliance

|

TMDL

Analysis

|

Trend

Analysis

|

Trophic

Status

|

Load

Analysis

|

Model

Support

|

Use

Attainment

|

Effectiveness

of CSO

control

measures

|

Indicator

of

Water

Clarity

|

Nutrient

Cycling

|

Habitat

Conditions

|

Lake Ecology

|

|

Chemical

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alkalinity

|

L, T

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bacteria

|

L, T

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOD-5

|

L, T, R

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carbon

|

L, T, R

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cyanide

|

T

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mercury

|

L, T

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Metals/Salts

|

L, T, R

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nitrogen

|

L, T, R

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

Phosphorus

|

L, T, R

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

Dissolved

Silica

|

L,T

|

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

Solids

|

L, T, R

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sulfides

|

L

|

|

|

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dissolved

Oxygen

|

L, T, R

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

Salinity

|

L, T, R

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

Physical

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conductivity

|

L, T, R

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LiCor

illumination

|

L, R

|

|

|

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: MCWB01114_0000[1]](Rev%202_Nov2010_files/image014.gif)

|